Stargazer: Van Gilmer

Van has been Director of Music for the Bahá’í House of Worship in Illinois since 2005.

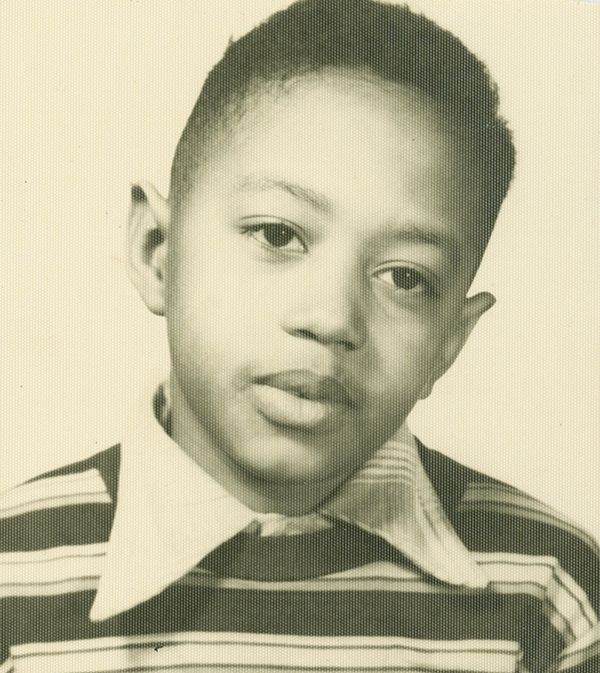

Can you imagine not being able to go to a certain school just because of your race? What if you weren’t allowed to go into a restaurant? Van Gilmer faced such injustices growing up in North Carolina, U.S., in the 1950s. From his teenage years on, he’s worked for racial justice.

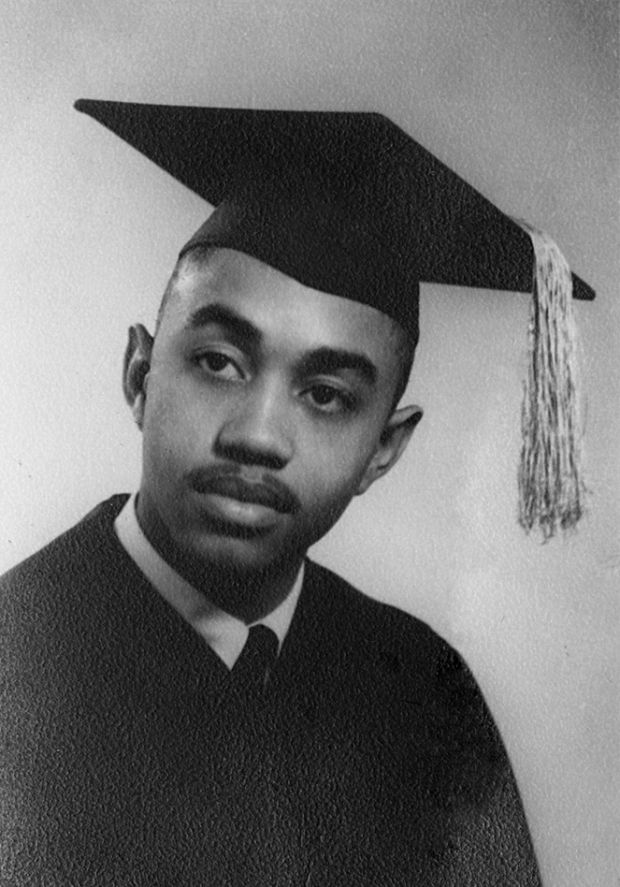

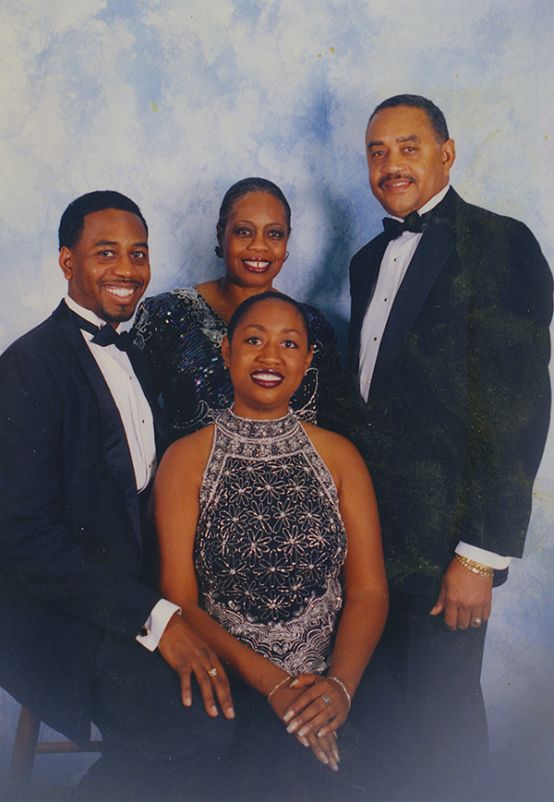

Van loved singing and playing music as a kid. He was also fascinated by art and architecture, and earned a degree in architectural engineering. In college, he went to Bahá’í meetings that were open to diverse people. At age 21, he became a Bahá’í. He worked as an engineer for the U.S. Navy for 37 years, performing music in his free time. In 2005, he became the Director of Music for the Bahá’í House of Worship in Illinois. He created the annual Choral Festival, which attracts 1,500 visitors from around the world. He’s toured internationally and performed at Carnegie Hall in New York. Van lives in Illinois and continues to build race unity.

Q: What’s your favorite childhood memory?

The warmth of the community. I mean, we knew everybody on the street ... I knew all the kids. We played. We weren’t distracted by things like television. We pretended a lot. Always good things—you know, being super[heroes].

Q: What experience from your childhood set you on the path toward your current career?

I was a little boy singing all over Greensboro. I was known in the community ... I sang solos for big groups of people—banquets, funerals, weddings ... I was taking piano lessons [and] learning to read music.

Q. What were your earliest experiences with racism?

When Van was about nine years old, he sometimes rode a bus into the city with his grandmother. Reactions from white passengers gave Van his first taste of racism.

When I had to start moving into areas where there were white people, and I’d have to act differently ... My grandmother would hold my hand and lead me to the back of the bus through these white people ... some acting like you weren’t even existing ... [I thought] don’t bother them, don’t gaze, move fast, and get into your place in the back ...

I learned that white people had a much fancier place to drink water, and that the doors that said “men” and “women” did not mean [me]. That water fountain was dramatic, because it had “colored” over one and “white” over the other. The bathrooms didn’t. They were hidden in closets where the black workers went.

Q: What do you do as director of music at the House of Worship?

[I direct the choir] three Sundays a month, and for other things the National Spiritual Assembly would ask us to sing for. Music is the highway to the soul and the heart. Music lifts the spirit and hearts ... If you can somehow share music with people, you might be able to get them to listen to what you have to say. Sometimes you say to them what you sing to them. And that’s been my philosophy ... Let’s try to find the words that will reach right into the heart and the spirit of the people who are on the floor in the House of Worship.

Q. What do you love about gospel music?

Gospel music is intimately tied to black people in so many ways, because it has a beat. It sets a mood ... Those who sing it make it up as they go. They do it as they feel it.

Q. This issue of Brilliant Star is about uprooting racism. What can kids do to work against racism in themselves and others?

Van graduated from high school at age 17, and then earned a bachelor's degree in architectural engineering at North Carolina A&T State University.

Most [white] people who are not Bahá’ís don't have any contact with black people. And so they are learning as adults what it’s like to be around somebody who is black. We’ve got to do more at constructing it, not just trying to hope that it will happen. Maybe you do that by making sure you’ve got a black family anywhere around you ... You can eat dinner together or you can go to a picnic and be together. Be familiar with how different we can be—and yet be the same. It’s still an experience we have to make, because it doesn’t easily happen, until we’re comfortable with our coming together.

Q: How would you describe the purpose of the civil rights movement to kids?

I would describe it as beginning to stand up for the rights of all people, to be able to do anything they want to do.

Q: How has the Bahá'í Faith influenced your career?

Its influence was learning to be with white people. When I came to work, I had already had experience of knowing white people, which was kind of unusual ... It was being comfortable with them, feeling like I am just as equal as you are. The Bahá'í Faith molded me for being a better person in the beginning of integration in America.

Q: If you had one wish for Brilliant Star’s readers, what would it be?

I wish they could ... learn about the Faith and celebrate it using their culture, not somebody else’s culture. I can be a Bahá’í, but I can also be a Haitian and Bahá’í. I can be a Ugandan Bahá’í ... We don't have to all look alike. We don't have to all pray alike. We don't have to all sing the same song, the same way.

In the early 1990s, Van and his family—his son, Sean; his wife, Cookie; and his daughter, Kimberly—began performing together as The Gilmer Family.

Portrait by Joyce Litoff